Managing large vessels involves significant operational and environmental responsibilities, with biofouling posing a critical threat to efficiency, safety, and regulatory compliance. Below are a few facts addressing key aspects of biofouling.

Biofouling Growth Dynamics

For Moving Vessels, microbial biofilms (slime) begin forming within hours, with visible clusters observed within 5–10 days under warm water conditions (>15°C).

Macro-fouling (barnacles/algae) becomes significant within 2–6 weeks, with barnacles growing ~0.1 mm/day in warm waters.

Ships stationary for 14+ days face high barnacle colonization risk, with significant growth observed within 3–4 weeks. During the 2020–2021 port congestion, vessels idling >30 days saw ≥20% hull coverage of hard fouling.

Biofilms form 2x faster in tropical ports (e.g., Singapore, Panama Canal) due to warmer temperatures (>25°C).

Consequences of Biofouling

Thin slime layers (0.1–1 mm) increase hydrodynamic drag by 20–25%, directly raising fuel consumption.

Calcareous Growth (1–5 mm) raises fuel consumption by 30–55% for average container ships.

Heavy Barnacle Fouling (>5 mm) causes power penalties of 60–86% at cruising speeds due to extreme drag from barnacle roughness. For a VLCC burning 100 tons/day of fuel, biofouling adds $3–6 million annually in extra costs.

Microbial-induced corrosion accelerates hull degradation, particularly in ballast tanks and welded joints. Salt deposits and anaerobic bacteria create localized pitting, reducing structural integrity by up to 30% over 5 years.

Fouling in seawater intakes reduces heat exchanger efficiency by 15–30%, risking engine overheating.

Non-compliance with IMO Biofouling Guidelines (MEPC.378(80)) incurs fines up to $250,000.

Biofouling-related fuel waste increases CO₂ emissions by 150–300 tons/day for VLCCs, complicating compliance with IMO’s Carbon Intensity Indicator (CII) and the EU’s FuelEU Maritime Regulation.

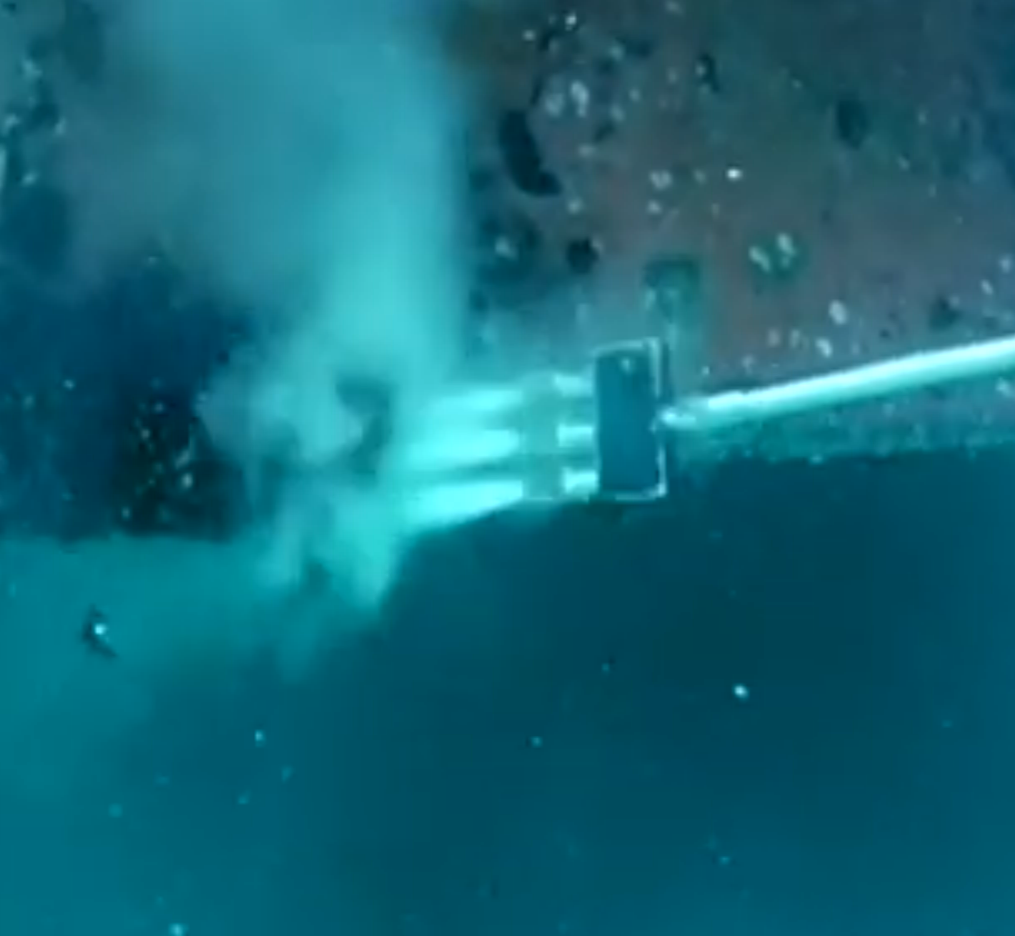

And we’ve got evidence that in some of the most severe cases, biofouling even spreads to the crew (see the last photo).

Cleaning

IMO recommends hull inspections every 6–12 months, with in-water cleaning if fouling exceeds 5% coverage. High-risk ports (e.g., Busan, Ulsan) enforce stricter protocols.

We recommend proactive cleaning every 3–6 months, which results in direct fuel economy.

Dry-docking costs millions of dollars, with 10–14 days of operational downtime. Infrequent dry-docking cycles allow hidden corrosion and structural weaknesses to accumulate.

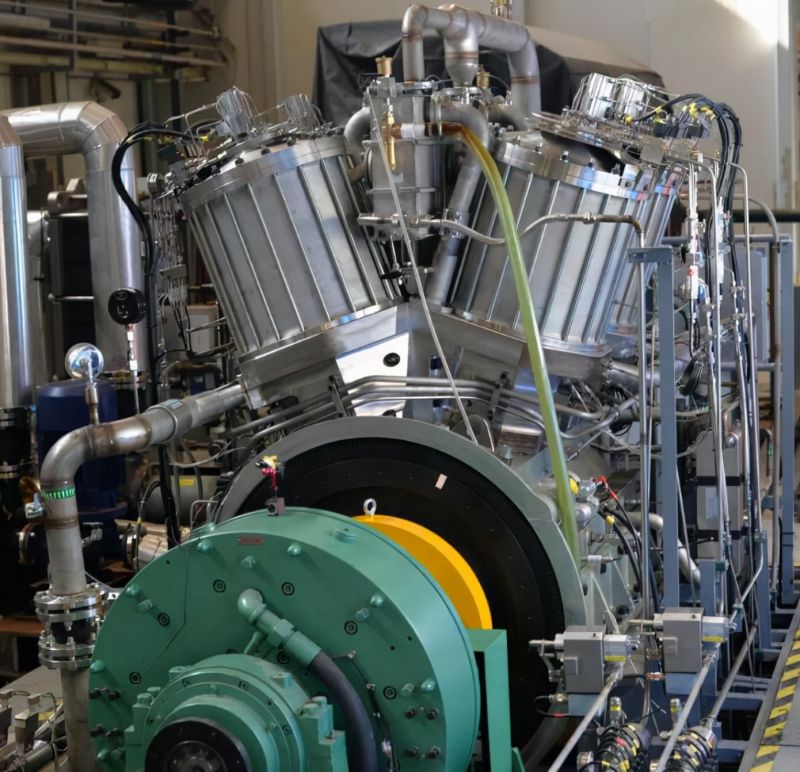

Robotic systems (e.g., our Crab robot) clean 1,000–2,000 m²/hour at a cost of tens of thousands of dollars and can clean most of the hull within hours.

Different in-water-cleaning methods vary in effectiveness and can impact the integrity of vessel coatings, but we can explore these aspects in future posts

If you’re interested in cleaning your vessel, please get in touch with us.

May your robot fleet be with you.