The 1981 recovery of 431 gold bars (£45 M value) from HMS Edinburgh, lying 800 ft beneath the Barents Sea, stands as a milestone in deep-sea engineering. Torpedoed by U-boat U-456 in April 1942 while carrying 465 Soviet gold bars as payment for lend-lease war supplies, Edinburgh sank with 58 of her crew. Nearly four decades later, a consortium led by Keith Jessop undertook a meticulously planned, technically groundbreaking operation under a “no cure, no pay” contract.

Preparations

Early challenges included sub-zero Arctic waters (1 °C), force 8–9 gales, penetrating 4-inch armored plating, respecting the wreck as a war grave, and managing crushing pressures of around 24 bars. Success hinged on merging cutting-edge survey, diving and gas-management technologies.

Years of pre-expedition research drew on Admiralty records, survivor accounts and HMS Harrier sightings to define a search area, while diplomatic channels from the 1950s finally secured Soviet agreement.

Detailed drawings of Edinburgh’s bomb room and gold-rack layout, obtained via special access to HMS Belfast’s plans, enabled construction of a full-scale model to train saturation divers on passageways, silted compartments, and fuel-tank hazards.

Salvage Operation

In April 1981 an OSA survey vessel used echo sounders and powerful sonar to detect the wreck on 14 May. A million-dollar ROV equipped with TV cameras, sonar, floodlights, Decca Hi-Fix navigation masts on Norway’s coast, and early GPS then mapped torpedo damage and the intact bomb room before any diver descended.

By August the DSV Stephaniturm, equipped with computer-controlled dynamic positioning and three thrusters, maintained station above the port-side hull. Saturation divers lived compressed in steel chambers for up to 38 days, entering the 1 °C seabed in heated suits via a two-man bell.

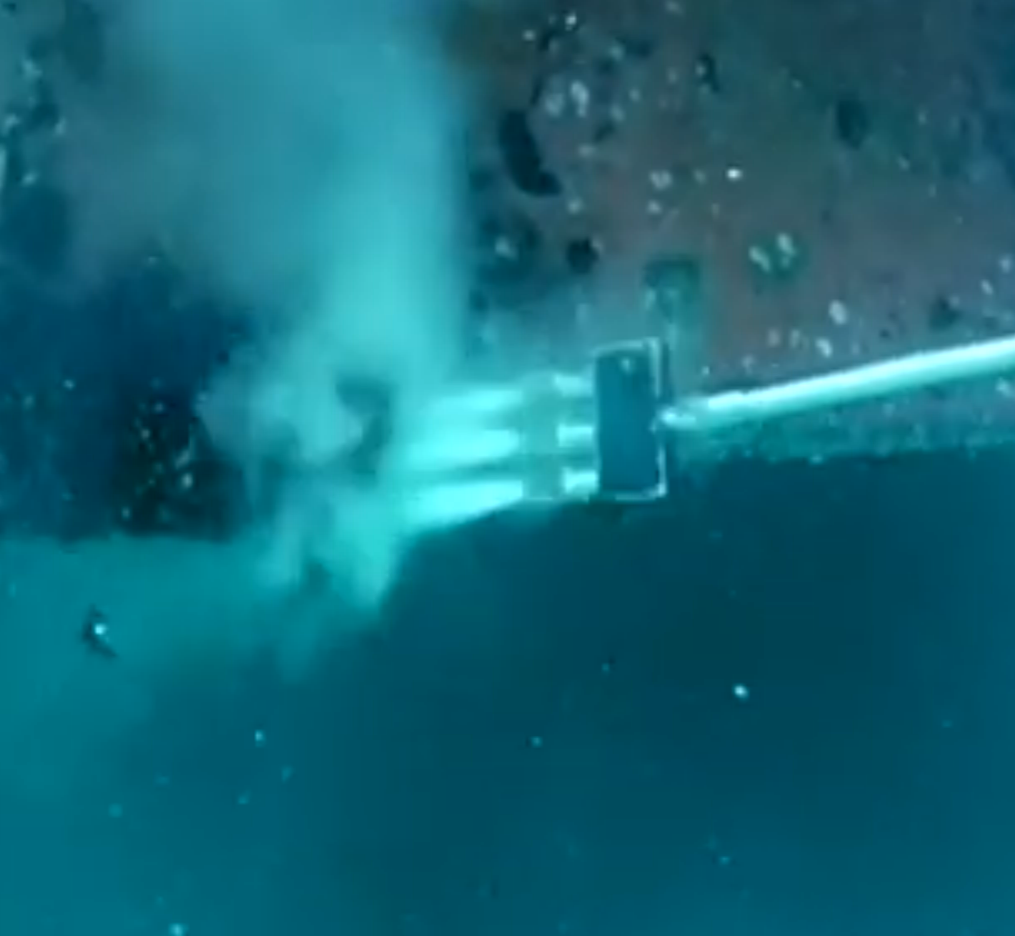

When it came to accessing the gold, the team rejected traditional “blast and grab” methods and instead used precision underwater cutting techniques Saturation divers employed oxy-arc cutting torches to slice through four-inch hull armor and adjacent fuel tanks, carefully navigating live ammunition and silted corridors to reach the bomb room. This approach preserved the integrity of the war grave, taking a full week to cut through the outer hull and fuel tanks to reach the bomb room.

The Gasmizer Reclaim System recycled over 90 percent of divers’ exhaled helium-oxygen mix through CO₂ scrubbers and water traps, while the Helinaut valve regulated helmet pressure. This innovation cut gas costs by £75 000 and extended bottom times, making the deep operation economically viable for the first time in history.

Ric Wharton of Wharton Williams later reflected: “The Edinburgh job proved gas reclaim’s commercial value - without it, we’d have needed endless helium shipments”

Life support systems were equally advanced. The Helinaut valve regulated helmet pressure while recycling breathing gas, and computer-controlled dynamic positioning kept the support vessel Stephaniturm precisely stationed above the divers, who worked in specialised heated suits.

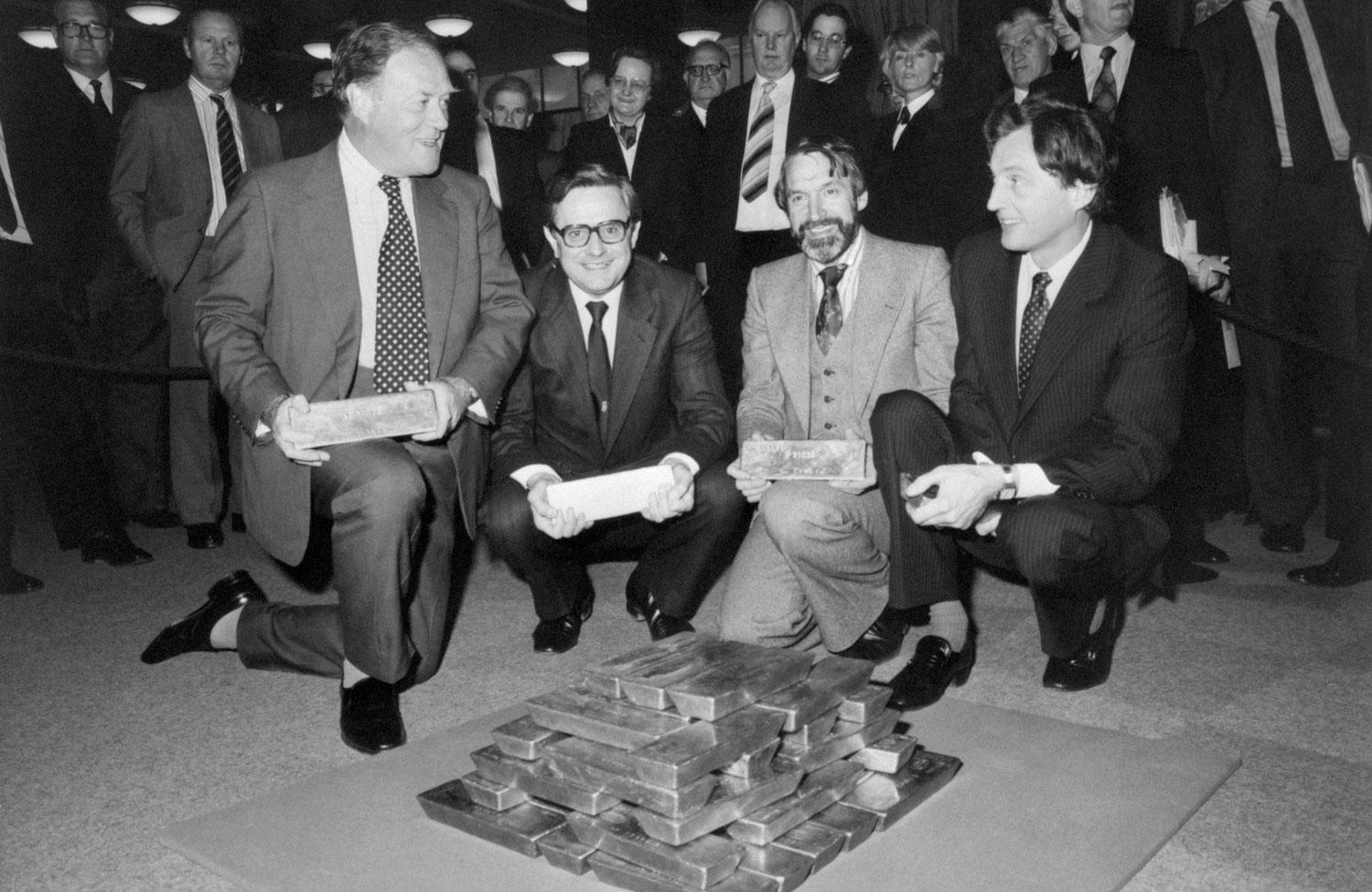

On 16 September diver John Rossier located the first 23-lb ingot, hoisting bars in wire cages. Amid deteriorating weather in October, 431 bars had been recovered before operations paused. A 1984–86 return yielded 29 more, leaving five ingots too costly to retrieve.

Results

The operation achieved a 93 percent recovery rate with zero injuries, established the 80/20 profit-split standard for salvage contracts, and proved that ROVs and gas-reclaim technology could supplant high-risk diver-only methods. The DSV Stephaniturm’s dynamic positioning and the evolution of the JFD Divex Ultrajewel 601 reclaim helmet trace directly back to lessons learned on Edinburgh.

Gold was split between the UK and USSR, with 45% awarded to the consortium. Post-recovery, bars underwent assay at Rothschild & Sons to meet London’s “good delivery” standards, avoiding costly penalties.

The Stephaniturm’s dynamic positioning and the ROV’s imaging capabilities became blueprints for modern offshore projects. From GPS-guided thrusters to reclaimed helium, every innovation turned a war grave into a beacon of engineering audacity.

“The Edinburgh operation taught us to treat the abyss as a collaborator, not an adversary. Every current, every pressure reading became data to exploit.”

Senior ROV Pilot, 1981 Mission Debrief

Image sources: National Museum of the Royal Navy, Imperial War Museum, PA Images/Alamy, and official public archives.